Halo of Confusion: Why Some Smart People Entertain Darwinian Doubts (Part 1)

Photo by Frank Cone from Pexels

14 minutes

Introduction

Darwinian ways of speaking and explaining often leave a bad odor in the minds of careful reasoners. These come away from any evolutionary discussion with the general sense that there’s “something there,” but that a trick of some kind has been pulled. Not wishing to sound uneducated, and perhaps knowing the enthusiasm with which Darwin’s partisans tear apart their critics with the glee of crazed chimpanzees, many choose to keep their skepticism to themselves. After all, no thoughtful person wants to be seen as an unscientific ignoramus, or a religious kook.

In my opinion, there are very good reasons for accepting the proposition that most organisms on earth have arisen through a process of descent with modification. The best indications of common descent are found in biogeography, molecular biology, and genetics. In the latter case, the evidence of shared retroviral DNA between humans and chimps is hard to gainsay. We won’t look at all of these indications here, but I mention them only to point out that there are facts that on their own – that is, apart from the logic of Darwin’s theory – point to common descent. However, my object in this and the subsequent essay is to deal with the evolutionary arguments and evidence that are usually put forth in public, and to show that they contain a lot of unreason and verbal self-deception, which qualities are the real reason why Darwinism gives many intelligent people pause. I’ll conclude that the best arguments for common descent are also compatible with (and, perhaps, suggestive of) a purposive view of evolution.

Before diving in, let’s briefly review the Neo-Darwinian account of common descent:

1. As organisms in a given population multiply and reproduce, changes (mutations) are introduced into their genes.

2. Occasionally, these changes confer traits that increase the likelihood that a given organism will survive long enough to leave offspring.

3. Over time, individuals with this beneficial trait leave more offspring than those without it.

4. Thus in nature there is a process of compounding the strongest traits and culling the weakest, which process, though totally unconscious, is analogous to a human breeder’s deliberate selection for the traits she finds desirable.

5. This very same “natural selection” not only conserves the strongest variants in a population, but, over time, it also compounds these traits to the point where an entirely new breeding population may emerge that is no longer capable of breeding with the parent stock, and which is therefore, by a certain definition, a new species.

6. This process of compounding changes also produces all of the elaborate qualities of every organism, and all of the variety within the kingdoms of life, and it does so in a stepwise fashion, but one in which no step is performed in light of the previous steps, nor in anticipation of any future step.

I. Darwinian Verbal Sleight of Hand

1. Time Doesn’t Help

You may notice that I left out one component from the standard account: time. Darwinists always make sure to mention that all of the above is supposed to happen over millions and millions of years. While I don’t dispute the millions of years, I note that ‘lots of time’ adds little to its explanatory value. The process above must make sense on its own terms. It must be a feasible mechanism for accomplishing #6 above. Padding the explanation with lots and lots of time may provide some psychological comfort to those who wish to believe it, but more time does not make impossible things possible.

For example, if my five-year-old lacks the wherewithal to organize, vacuum, and dust the whole house, it does not make sense to say that given millions of years, he would eventually do it. Were he frozen for several eons at his current level of ability, and set loose on the house, would accomplishing what is beyond his capacity suddenly become more possible? Likewise, if we’re going to say that uncoordinated, stochastically isolated changes collected together and compounded by natural selection will eventually “add up” to coordinated and purposively organized organs, adaptations, and organisms, then that assertion must make sense in-and-of-itself. Adding time does not add real plausibility to something that is fundamentally implausible. The appeal to time then is a kind of verbal sleight of hand.

2. Just-So Stories

Now an organism by definition is an organized, living whole whose various component parts together constitute its unity. What is true of the organism as a whole is also true of each of its organs, life systems, and even its cells. So how do Darwinists explain the emergence of one of these systems in terms of a mechanism which eschews all coordination? Strangely, by starting at the end (the desired conclusion) and working their way back to the beginning. For example, called upon to explain the appearance of flight, the Darwinist proposes all sorts of isolated changes that gave rise to such things as feathers, hollow bones, skin membranes, etc. He then tells a story about how each change would have been useful on its own, and so would tend to be “selected for” (meaning, in English, that those organisms that had it had more young.) He then constructs a series of hypothetical organisms that would have had to exist in order to get from point A to point B. Now since point B, a flying, feathered reptile (for example) has certain obvious advantages over point A (a non-flying reptile), and since natural selection tends to preserve organisms with advantages, it therefore follows that it would have tended to produce B. After all, it did! And there you have it.

Now the issue that many people have with this sort of reasoning is that it seems circular. After all, any possible organism must have features that allow it to survive and reproduce. If common descent is true, and more or less stepwise, then it must take place in a series of viable steps. But this means that a similar story can be constructed after the fact for almost any possible state of affairs. No matter what organisms exist, or have existed, it will always be possible to start at the end and work backwards in order to construct a narrative whereby B emerged. One can then plausibly claim that evolution would have “favored” B, because B’s adaptations conferred an advantage. (I mean, they must have, or B wouldn’t be here in the first place!) In some cases, parts of these stories can be checked out. In other cases, the fossil record won’t allow that. Either way, it will usually be impossible to prove one of these narratives wrong, since the absence of evidence isn’t evidence of absence.

Tiktaalik; a fish-amphibian with lungs and gills. (By Eduard Solà - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0)

But I am not here concerned with supposedly missing intermediate forms. Once a person has strong independent grounds for believing in some process of macroevolution, however mysterious, it follows that the intermediate forms have to be somewhere. In many cases, stunning intermediate forms have indeed been found. What concerns me rather is this practice of “explaining” by starting at the desired conclusion, and working back to the premises necessary to make it true. The desired conclusion is always the same: This organized, coordinated thing was brought about by the compounded association of numerous unorganized, uncoordinated things. Now what do I have to say in order to make that true?

And the problem is this: we only know that the steps from A to B were individually adaptive. We don’t know – apart from the demands of Darwinist theory —that the process as a whole wasn’t organized and coordinated. The evidence of nature does not tell us that the process was directionless and accidental; it only shows us lots and lots of viable organisms, each of which had a particular, contextual cause for being the way it is. These things, considered on their own, and also considered in light of their overall trajectory, could just as well suggest an orderly, purposive path. The fact that the individual adaptive steps do not “see” the morphological trajectory over time does not mean they don’t take place in light of such a trajectory. That trajectory may be built into the system as a whole. More on this later.

To see the above point in another way, suppose a clever engineer had before him two vehicles, a speedboat and a submarine. A lay person like myself could hardly imagine a viable path from one to the other; let alone a path in which each stage served a function. But our brilliant engineer knows one (even two!) ways to turn the speedboat into a submarine and get use out of each intermediate stage, such that each step has its own, context-dependent reason for being. Now if we imagine arrayed before us from left to right, all the stages from speedboat to submarine, would this progression itself seem arbitrary and uncoordinated, or rather brilliant and purposive, all the more so because each intermediate vehicle had its own practical function? The question answers itself. Turning back to our non-flying to flying reptile sequence, does a succession of viable organisms between them seem more random or more directional? Be honest.

3. “Teleonomic” Language

At this juncture, the Darwinist will say that I am confused. “Evolution does not see ahead!” he will say. “You are reading teleology into the process.” And on this point I am doubly annoyed. First of all, it is evolutionists who are constantly employing teleological language to describe this “mindless” process. Even when trying their darndest not to be teleological, Darwinists seemingly cannot relate the process of natural selection without actually suggesting that nature is selecting things. Perhaps this is because the explanation loses some of its power to explain as soon as intentionality is subtracted. If you say, “evolution selected for gliding, because gliding helped this organism escape predators,” then you are saying something meaningful, but only if you keep intact the idea of ends. It’s very difficult to know how to convey the same content without the language of intentionality. Let us take this classic passage from The Origin of Species, and then strip out all the intentional language, to see if it still conveys the same meaning its author intended:

It may be said that natural selection is daily and hourly scrutinising, throughout the world, every variation, even the slightest; rejecting that which is bad, preserving and adding up all that is good; silently and insensibly working, whenever and wherever opportunity offers, at the improvement of each organic being in relation to its organic and inorganic conditions of life.

Stripped of teleonomic language:

Daily and hourly, throughout the world, even the slightest variations that confer an advantage for survival confer an advantage for survival, while those that don’t confer an advantage for survival disappear over time. All of the traits that survive are insensibly added up, whenever and wherever this can happen, with the result that living beings become better at surviving in their organic and inorganic conditions.

To me, the second statement lacks much of the punch of the first. It takes away the suggestion of molding and shaping towards ends, and leaves only a description of some things dying, and some things not dying. It reveals natural selection as something like a truism of nature. “Whatever works, works, and will go on working as long as it does, until it doesn’t.”

4. Confusion About Teleology

Second of all, it is the evolutionist who is confused when he says “evolution doesn’t see ahead!” What he means is that the process of death and breeding that he personifies as “natural selection” does not “see ahead.” But evolution (or macro-evolution and common descent) is logically separable from the Darwinian mechanism. Even if mutation-plus-natural selection is the only “mechanism” at work in macroevolution, it is logically possible that the process as a whole is ordered toward ends, even while its component parts are not.

For example, it could be that the various forms of life are somehow virtually present in the structure of matter-energy, much the same way that the stable and unique non-living chemical substances are virtually present in the potentialities of sub-atomic matter and energy. Theoretically, at least, the universe as a whole could be a kind of collective mind, or it could be observed by a mind or minds who collapse the wave functions of “random” mutations, giving change a definite direction, or it could be a kind of life-producing theater. Or something even weirder may be at play, such as the perceived needs of organisms somehow influencing the potential changes in the genome, as seems to be implied by certain epigenetic effects whose mechanism is not well understood.

Whatever the case may be, a succession of viable changes which just happens to result in what appears to be a meaningful directional movement may actually be a meaningful, directional movement, even if the component parts do not comprehend or “aim at” that movement. Such is the case with any piece of music, work of art, bodily organ, or machine parts, or the parts of an acorn which do not “comprehend” the oak. From the non-directed-ness of individual parts, one can conclude nothing about overall directedness, or the lack thereof, of nature’s processes. And if that trajectory looks and behaves like a sort of biological symphony, unfolding over time, somehow repeatedly reaching meaningful ends, it’s possible that it is a kind of symphony. Some would even say that this is the more natural way to interpret the progression of the “notes” that make it up.

Of course, all that has been said so far assumes the basic soundness of natural selection as a mechanism, but a closer examination reveals that this “mechanism” is rather vague.

II. Natural Selection Deconstructed

A note on terminology. Biologists use natural selection in both a broad and a narrow sense. Broadly speaking, natural selection is the whole process by which certain traits arising through chance mutations are preserved because they confer some advantage in survival, and therefore in reproduction. More narrowly, natural selection refers to just the “selection” part of the mutation + selection mechanism. There are also a number of supplemental selection “mechanisms,” such as sexual selection, which are really just special instances of the same logic. I will use the terms contextually and interchangeably here, just as Darwinists regularly do, trusting in the charity of my readers to understand the sense I intend. With that in mind, let’s look at natural selection, and at some of its supporting concepts.

1. The Mechanism

Besides the normal processes of shuffling and recombination that happen when organisms reproduce, there are also novel changes to the genes. For the sake of brevity and in order not to go down a rabbit hole, I will set aside the question of what percentage of these changes are either meaningless or damaging, and what percent are potentially helpful. Suffice to say that if common descent is true, then helpful novel traits arise in the genome somehow. We will assume for the sake of argument that these are largely random, meaning that their outcome cannot be predicted in advance. These changes are called mutations.

Now suppose that one of these changes results in a trait that causes its possessor to leave more offspring than its conspecifics, and the same change is then passed on to those offspring, This novel trait is said to have been “selected for.” The idea is that the overall press of nature on ever-changing organisms has a weeding and focusing effect such that some traits are conserved, other (novel) traits introduced and preserved, and still others weeded out, and that this total situation is analogous to artificial breeding. Darwin and Wallace’s big idea was that this very same process, extended over time, also produces the whole panoply of living organisms from a few simple organisms.

Now the interesting thing about this mechanism is that once you understand it, it does immediately make sense of a lot of disparate data. Fluctuations in populations of finches, or of moths with certain colorations, or the hyper-specialization of certain animals to certain plants, all suggest a process of constant mutual adaptation, which dynamism also requires the capacity of organisms to be reshaped over time. This is just as Darwin and Wallace said.

Yet the mechanism is still logically problematic in other ways. For one thing, nature can only “select” what mutation has already provided. Consequently, mutation, not the anonymous survival styled “selection,” is the real engine of evolution. And this is a point that is always getting lost, because of the above-mentioned tendency of Darwinists to personify and reify “selection.” Only changes in the genes actually matter, for blind nature cannot (according to Darwinists) draw out any particular change, nor see the big picture, nor string changes together purposefully. I believe this is a point on which Darwinists actually confuse themselves. They are so in the habit of imagining natural selection as a kind of meta-mind, that they forget that they aren’t supposed to think of nature as having any kind of mind or intentions. They then accuse their critics of misunderstanding a mindless process as intentional; meanwhile, they constantly speak as if it practically were intentional.

The next problem is mutation itself. What does the word really mean? Well, we could list here all the known and documented types of genetic mutation, but this isn’t all that helpful. Darwinists believed in variation/mutation long before this or that type of mutation was discovered, and they are philosophically committed to believing in whatever sorts of mutations must be necessary to produce novel traits, whether or not they’ve yet been discovered.

The problem here is that the word mutation is a kind of paper slogan. It does not specifically mean “point mutation,” “chromosomal doubling” etc. At the level of theory, it means “whatever changes had to happen such that X trait could arise.” And that would be fine, if it were frankly admitted. But to admit that would be to admit that “mutation” is not a specific thing so much as a logical placeholder. It’s a meta-mechanism; something like aether or phlogiston, that must be there. Mutation is an ontological pronoun for “whatever it was that happened such that new, beneficial traits arose in the genome.” In specific cases, a particular change might be explained in terms of a particular, independently known class of mutations. But in general, the term is a catch-all for “helpful, novel information.” Thus there is a kind of vague circularity built into the very business-end of the theory. And it’s not the only one.

2. Circularities

Darwinism is plagued by circular language, but not the obvious kind. If a person says to you: “I know my sister is telling the truth because she says she’s telling the truth,” we can easily see the problem. But if someone says, “Everyone in this room is wearing a hat. John is in this room. Therefore John is wearing a hat,” the circularity is not as obvious. If John is part of the class “everyone in this room,” then he was already included in the major premise. It amounts to saying, “The people in this room — John, Bill, Sarah, and I – are wearing hats. John is in this room. Therefore John is wearing a hat.” This may be a harmless, run of the mill circularity, but there are cases where the circular reasoning can be quite deceptive, especially, perhaps, to those employing it with sincerity.

Darwinian circularity appears most prominently in its use of homology, cladistics, and the notion of survival of the fittest.

Homology

Systematics is the scientific classification of organisms. It includes terms of comparison and categorization that are meant to distinguish degrees of sameness and difference among organisms, and to differentiate real structural similarity (homology) from mere superficial similarity (analogy.) Structures are homologous when they are variations of the same type or theme. The hands of a man, and the wings of a bat are an example of homology. Two structures are only analogous when they perform the same or similar function, but are built on an entirely different design: the wings of a bat and the wings of a butterfly, for example.

Even before Darwin, taxonomists grouped organisms by degrees of relatedness based on homologous structures. Thus men and chimpanzees were more closely related than men and horses, while men and horses were more closely related than horses and komodo dragons, and horses and komodo dragons were more closely related than komodo dragons and jellyfish, and so on. Based on homologies, men and whales were more closely related than whales and fish, despite the latter two being more superficially related, and having many analogous structures (such as fins.) Homology in-and-of-itself, has to do with structural unity, with the relationship of two organisms or organs as ideas. It is thus logically separable from the idea of ancestral relationship. For example, one could employ some of these concepts to draw up taxonomies of vehicles, assigning them to species, genus, order, and so on, based on homologous structures, without any suggestion of ancestral relationship.

Now Darwin proposed to account for homologous structures in terms of the mechanism of descent with modification via natural selection. Thus two organisms had homologous skeletal features because they were related by descent. Men have five fingers, and bats five “fingers' ' because they shared a common ancestor that possessed that trait. Now this explanation for what causes homology, true or false, is not logically problematic. The problem arises when Darwinists use homology as evidence for common descent, while also defining homology as a pattern of common descent. This amounts to saying, “Homologous structures show common ancestry because homology is a pattern of common ancestry.”

Careful readers, exploring the proofs for evolution found in standard textbooks or science programs, detect that some kind of verbal trick has been pulled, even if they can’t put their finger on what it was. Meanwhile, people who know that Linneaus, the father of systematics, classified man as a primate, but did not believe in common descent, might well detect a practical contradiction here. If homologous features just are shared ancestral features, how on earth did Linneaus know that man was a primate, or that whales were mammals?

Cladistics

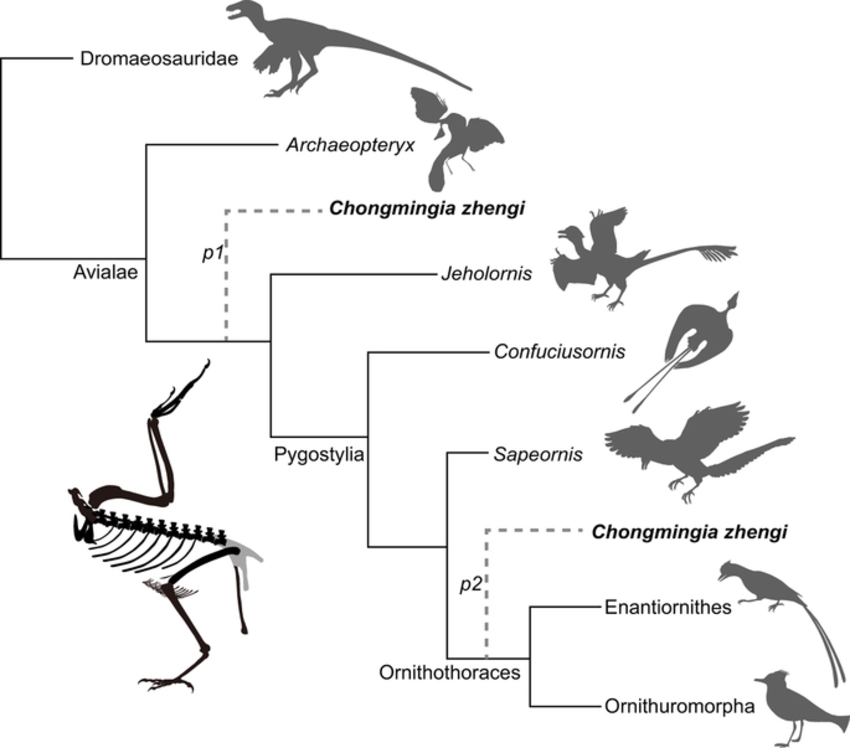

Cladistics, a popular evolution-based taxonomic system, takes this error and compounds its circularity. It eschews traditional Linnaean structural classification for a system that purports to group organisms in clads based on shared ancestry. Thus, for example, it places birds and bird-hipped dinosaurs in the same clad, eschewing the general typological category of “reptile.” The problem with this approach is two-fold. First, it confuses essence (what a thing is) with origin (what caused a thing.) Second, it involves another practical circularity. How do we know where birds came from? Why, by constructing ancestry trees based on their shared structural features with non-birds. And how do we know what birds are? Why, by looking at the clad to which they belong.

Image by Min Wang at Researchgate.net

This not only leads cladists to make bizarre statements such as, “Chickens are dinosaurs,” but it also means that cladistics relies parasitically on Linnaean classification to provide the very structural categories that it then defines away. Cladistics is a great example of the persistent Darwinian habit of “proving” something by simply defining it into existence. And in this it resembles the last of the circularities we’ll consider: “fitness.”

Survival of the Survivors

The problem with “fitness”, and with the “survival of the fittest,” is that it’s a truism at best. A trait is considered to increase fitness if it causes its possessor to leave more offspring. Darwinists carefully note that fitness is not about being bigger, or faster, or smaller, or more camouflaged per se; but just about having the trait which in a given situation leads to leaving more offspring, and therefore outcompeting ones conspecifics. In other words, surviving. The term fitness has no meaning apart from survival. But in that case, “Survival of the fittest” just means “survival of the organisms that survive.” Without a criteria of “fitness” that can be defined independently of the term “survival,” “survival of the fittest” is just a tautology. At best it tells us the same thing that natural selection tells us, namely that an organism’s unique features help it survive. This is certainly useful – even indispensable – but it falls short of all semantic import that a phrase like “survival of the fittest” conjures up.

Now I raise these objections not simply for the sake of splitting hairs, but because the fallacies, imprecisions, and circularities considered in the abstract above conceal very concrete problems. These problems show up in most public expositions on the subject of evolution, and they help to generate the climate of distrust and confusion that hangs like a halo above this particular branch of science. In my next post I will illustrate some of these concrete problems, and I will argue that some of the best proofs of evolution-in-general (common descent) are not particularly Darwinian. I will also argue that Neo-Darwinian reliance on discredited proofs and lines of argument, and their sidelining of more interesting proofs of evolution, as well the Darwinian need for Young Earth Creationism as a weak foil, constitute the main reason that lots of educated, thoughtful people have doubts about Darwin. Stay tuned.

© 2021 Joseph Breslin All Rights Reserved